Uber’s latest quarterly figures are less severe than “multi-billion,” but still over $1 billion. From a 2019 second-quarter loss of $5.2 billion, Uber’s recent figures show an increase in rides and slowing of its money-burning since its inception. However, for anyone who initially invested in the company, reading that “improved” figures show a $1.2 billion loss for their last quarter remains a bitter pill to swallow.

Google, Amazon, Apple, Airbnb, Uber, and possibly WeWork have all made big impacts on our small globe, with the former showing us what novel thinking can earn in revenue, making it easier for the latter startups to glean venture capital in spite of the absence of any clear or enticing profitability.

Trading too heavily and often on the “unknown” of the future, where it’s assumed that consumers will “logically” line up to employ a service or buy a product, is a risky practice to rely on. The figures at play in many larger VC projects would make last century traders reach for the rescue remedy.

The old school doesn’t know, the young startups are dreaming wildly and vividly, and too much investment money flows in on the back of hope rather than solid projections.

Viable startup or bottomless hole?

Remember that, even scaled for inflation, the kind of venture capital budgets being allocated to tech startups this century dwarf anything seen before in the market. When you raise $6 – 7 billion, profitability is too easy to allocate a lesser profile than it deserves. The business mentality of “spend it so we can make money there” dominates when there’s such a large fund to draw on. Traditionally, the profit margin was the hard-nosed cut-off line that enabled raising capital. A very secure and detailed route to profitability had to be demonstrated before the capital was invested. That hasn’t been the case for some time now.

Part of the modern venture arena muddied by crypto token ICOs, nominal venture capitalists is caught between a rock and a hard place. Pressed to glean as much profit from investments as possible – and fully aware of the dramatic returns tech startups have enabled in the digital age – FOMO seems to alternate with a desperate desire for surety in current VC circles. Anyone looking to pitch a share offer now would do well to follow old school basics (adding in that tech flare, of course).

First and foremost, any business should find an IT support company in your local area. This crew won’t just layout needed hardware and associated IT that enables you to start up, but will also accurately depict future costs and needed expenditures based on a host of possible scenarios. Indeed, expanding IT is now on par with ongoing accounting as the two principal pillars of any tech startup.

Many times, after a great hoo-ha about remodeling the world and other millennial jargon, market realities never changed. It was never going to work. This is giving rise to a renewed insistence from investors and regulators in London and elsewhere. The second crucial point: don’t misstep on the basics. Now that trillions of dollars have been thrown at an assortment of mod startups over the last two decades, it appears there’s a limit as to how even billions of dollars can change the nature of your business.

Profit projections should still ideally conform to legacy protocols and depictions, without which, they’re just loads of guesswork.

Massive budgets and long-term profits

Uber is facing the daunting challenge of turning a profit by 2021, while simultaneously leaving themselves room to fail on the anticipated deadline. The lift-sharing company is facing the same issues as traditional taxi industries: low profitability in trying to be ‘all things to all people’, and constant tugging at the wage bill by drivers. The operators want more, consumers fiercely resist increases in fares, and Uber needs to keep business continuing as usual.

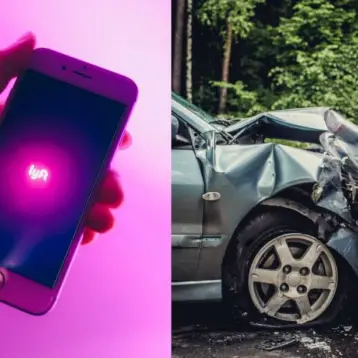

This is how a startup can burn through billions of dollars in a single year. It needs to be seen to be successful. More telling is that many competitive startups – think Lyft in North America – are facing the exact issue Uber is trying to solve: how to arrive at honest profitability. Lyft is aiming at first profitability in 2021. Wall Street remains broadly skeptical of both companies meeting their 2021 targets.

Vagaries in exactly how profits are to be attained are becoming warning signs for venture capitalists. In 2019, it’s become too easy to dream differently, dream big, and forget about whether the whole idea will turn an actual profit. Spooked by the 2008 collapse, and enabled by QE and other salvage policies, venture capitalists have had a rough ride over the last 10 years. Having been bandied about in the tech startup arena – with cryptocurrency thrown in for good measure – VCs are starting to feel more confident about insisting on traditional depictions of earnings, tech startup or not.

Caught between pressures and demands, will Uber turn a profit by 2021?

In the race to make things “new” and “different” to entice customers, many startups have hit the brick wall of fundamental market dynamics. Caught between downward pressure from consumers and rising demands from drivers all over the world for a bigger slice of the profit pie, Uber is realizing there was a reason the old metered taxi cab industry ran as it did for over a century.

Many other tech startups besides those currently making headlines have yet to turn a profit. Billions of dollars are at play in many of them. It’s perfectly fine to set aside huge spending budgets on startup technologies, but ultimately, only time will tell whether consumers adopt or deflate those dreams. Sharper pencils and greater transparency would serve both jittery VCs and legitimately valuable startups better right now than more of the blind hope that funded Uber and others like it.