|

A study on memory deficient mice was recently led by Larry Feig, professor of biochemistry at Tufts University School of Medicine. In the study, mice with a genetic defect that caused them to have memory problems and learning disabilities were raised in an enriched environment for two weeks during adolescence. As was expected, their memory was significantly improved – previous studies in the field have already established that enriched environments cause an improvement in brain functioning. The mice were then returned to normal conditions, grew up and produced offspring, who were subjected to various ‘intelligence’ tests. The experiment revealed surprising results – the enriched mice offspring showed higher scores on the memory tests than mice with the same genetic defect, whose mothers had not been exposed to an enriched environment.

Previously conducted research has shown that exposure to different conditions during pregnancy can affect the offspring. “A striking feature of this study is that enrichment took place during pre-adolescence, months before the mice were even fertile, yet the effect reached into the next generation,” said Feig.

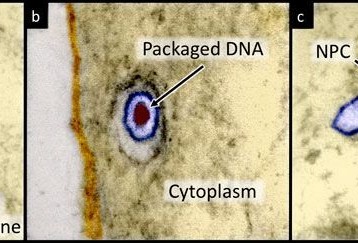

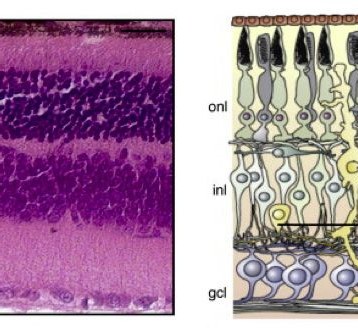

The research also tested a molecular correlate of memory called Long Term Potentiation (LTP). This is a mechanism that strengthens the link between two neurons when a memory is being created. The genetically impaired mice had a faulty LTP process. The enriched environment repaired the LTP function of the mothers and the fixed mechanism passed on to the offspring. “When you look at offspring, they still have the defect in the protein, but they also have normal LTP,” explained Feig.

It is also clear that the improved memory was not the result of being brought up by mothers with better memory. Some of the young offspring were separated from their birth mothers and raised by non-enriched foster mothers; however, their test results still showed equal memory improvement.

The idea of passing acquired traits to following generations was proposed by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in the 19th century, but eventually was dismissed when Darwin’s theory of evolution was commonly accepted by the scientific community. This idea is also contradictory to Mendelian genetics, which essentially state that an individual inherits qualities from his parents through specific DNA sequences. The type of inheritance shown in this research is usually referred to as epigenetics, or the environmentally-induced changes in the structure of the DNA and chromosomes which alter the way genes are expressed. Later on these changes may be passed on to the offspring.

Although the research was performed on mice, it is reasonable to assume that, at least in part, it may be applicable to humans. One of its important implications would be the understanding that girls’ education could be important not only for their own development, but also for that of their future children.

In recent years the debate between neo-Darwinism and neo-Lamarckism has heated up as more and more suggestions have been made that at least to some degree Lamarck’s ideas are not completely misguided. It is possible that the current research is just another example for a case where environmental factors can have biological consequences that are transmitted to offspring without a change to gene sequences taking place.

TFOT has recently covered the story of a research team from Bristol University, UK, that has identified molecular and cellular mechanisms important for recognition and memory. We have also covered a study conducted at the Weizmann Institute in Israel, in which scientists discovered an enzyme capable of erasing memories by disrupting the synapse maintenance.

If you want to read more on environmental influences, please visit the Tufts University School of Medicine news page.

Image icon credit: Aaron Logan