Pushing the Spitzer space telescope’s capabilities to a new level, astronomers now have improved their understanding of the earliest stages of planetary formation. The new information may shed light on the origins of our own solar system, as well as on the potential for the development of life in other solar systems. The information was obtained thanks to a new technique developed by John Carr of the Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, and Joan Najita of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Arizona. Carr and Najita managed to develop a new technique, which enables astronomers to measure and analyze the chemical composition of the gases within protoplanetary disks, using Spitzer‘s infrared spectrograph.

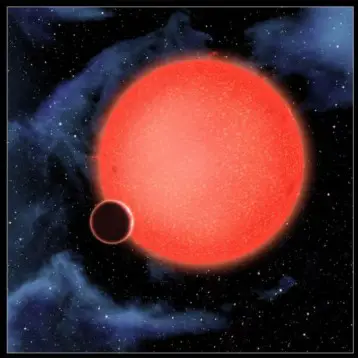

Protoplanetary disks are flattened disks of gas and dust that encircle young stars. Scientists believe they provide the building materials from which planets and moons develop and eventually, over the course of millions of years, evolve into orbiting planetary systems like our own.

The researchers explain that because most of the material within the disks is in gas form, it was difficult to analyze the different materials. Thanks to the new technique, scientists can finally study the gas composition in these regions, where it is believed that planets form. Up until now, astronomers focused more of their attention to solid dust particles, since they are easier to observe.

The region currently being studied is the protoplanetary disk around the star known as AA Tauri. Less than a million years old, this star is a typical example of a young star surrounded by a protoplanetary disk. Using new procedures, the researchers were able to detect the minute spectral signatures for three simple organic molecules, hydrogen cyanide, acetylene and carbon dioxide. Water vapor was also detected. It seems that these substances are more prevalent in the disk than in the dense interstellar gas called molecular clouds, from which the disk originated. “Molecular clouds provide the raw material from which the protoplanetary disks are created,” explains Carr. “So this is evidence for an active organic chemistry going on within the disk, forming and enhancing these molecules.”

Although Spitzer’s infrared spectrograph detected these same organic gases in a protoplanetary disk in the past, the implementation of the new methods for studying the primordial mix of gases provided the data necessary in order to establish the new discovery.

To date, astronomers know that water and organic materials are abundant in the interstellar medium, but have yet to establish what happens to these substances after they are incorporated into a disk. Nobody knows whether the molecules are destroyed, preserved, or enhanced within the disk. “Now that we can identify these molecules and inventory them, we will have a better understanding of the origins and evolution of the basic building blocks of life, where they come from and how they evolve,” say Carr and Najita. “With upcoming Spitzer observations and data in hand,” Carr adds, “we will develop a good understanding of the distribution and abundance of water and organics in planet-forming disks.”

TFOT has recently covered new information regarding the contribution of small stars to the formation of bigger stars, and covered the launch of the Space-Shuttle Endeavour. We also reported on the ultraviolet mosaic of the nearby “Triangulum Galaxy“, and on the latest research on the life cycle of neutron stars.

For more information regarding this latest discovery, see NASA’s website.