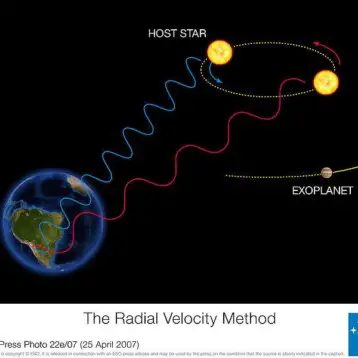

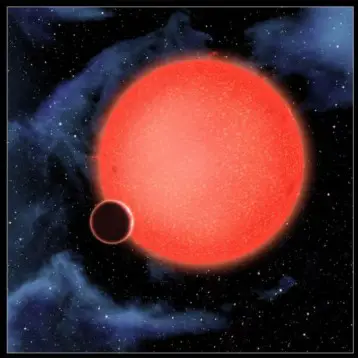

The star, known as EV Lacertae, was not considered by scientists to be extremely interesting. It is a red dwarf, the most common type of star in the universe. In comparison, our Sun shine 100 times brighter and has three times the mass as EV Lacertae. However, at a distance of only 16 light-years from Earth, EV Lacertae is one of our closest stellar neighbors. EV Lacertae’s constellation, Lacerta, is visible in the spring for only a few hours each night, and only in the Northern Hemisphere; had the star been more easily visible, the flare probably would have been bright enough to be seen with the naked eye, lasting for about two hours.

All this data explains why astronomers were so shocked with the flare’s ferocity. “Here’s a small, cool star that shot off a monster flare. This star has a record of producing flares, but this one takes the cake,” says Rachel Osten, a Hubble Fellow at the University of Maryland, College Park and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “Flares like this would deplete the atmospheres of life-bearing planets, sterilizing their surfaces.”

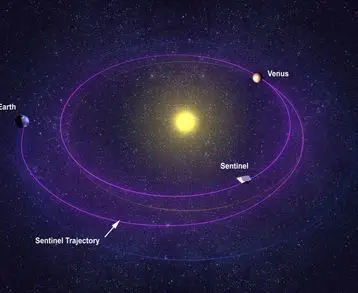

The flare was first observed by the Russian-built Konus instrument on NASA’s Wind satellite in the early morning hours of April 25th. Less than two minutes later, Swift’s X-ray Telescope caught the flare and quickly slewed to point toward EV Lacertae. The flare was so bright, that when Swift tried to observe the star with its Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope it shut itself down for safety reasons. The star kept emitting bright X-rays for 8 hours before settling back to normal.

Robert Naeye from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center says that EV Lacertae can be likened to an unruly child that throws frequent temper tantrums, since it has an estimated age of a few hundred million years – a relatively young age for a star. It rotates once every four days, which is much faster than the Sun (which has a rotation cycle of four weeks). Due to the fast rotation, strong localized magnetic fields are generated, making it more than 100 times as magnetically powerful as the Sun’s field. This energy – stored in the star’s magnetic field – is the power that generated these giant flares.

The flare’s incredible brightness enabled Swift to make detailed measurements. Since EV Lacertae is 15 times younger than our Sun, it gives us a window into our solar system’s early history. Since younger stars rotate faster and generate more powerful flares, scientists assume that in its first billion years the sun must have let loose millions of energetic flares that would have profoundly affected Earth and the other planets. Flares release energy across the electromagnetic spectrum, but the extremely high gas temperatures produced by flares can only be studied with high-energy telescopes, like those on Swift. Its wide field and rapid repointing capabilities make it ideal for studying such stellar flares. Most other X-ray observatories have studied this star and others like it, but they have to be extremely lucky to catch and study powerful flares due to their significantly smaller fields of view. “This gives us a golden opportunity to study a stellar flare on a second-by-second basis to see how it evolved,” says Stephen Drake of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

TFOT has also covered the discovery of life’s building blocks in Space, made by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, and the detection of the largest known comet outburst, made by the comet ‘Holmes’ in mid-October 2007. Other related TFOT stories are the observation of the youngest known pulsing neutron star, located in the constellation Aquila, and the discovery of a quadruple-star system, known as HD 988000, which may be the first planetary system with four Suns.

More information on the detection of the ‘monster flare’, can be found on NASA’s website.